A couple highlights, one dud, a disapointment, and a throwback.

Years ago – when I was clocking time at UPS before college – I was listening to an episode of Filmspotting, where they talked about director’s they’d give blank checks too. One of them was Joshua Oppenheimer, director of Indonesia genocide documentaries The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence (movies I both need to see and revisit, my younger self be cursed). They mentioned that one of the things the MacArthur Grant recipient was shopping around was a post-apocalyptic musical, a very leftfield choice and understandably one that was having difficulty getting funding. I subsequently forgot about it over the years as his documentaries placed on numerous decade lists, right up until it was announced to be showing at both Telluride and TIFF.

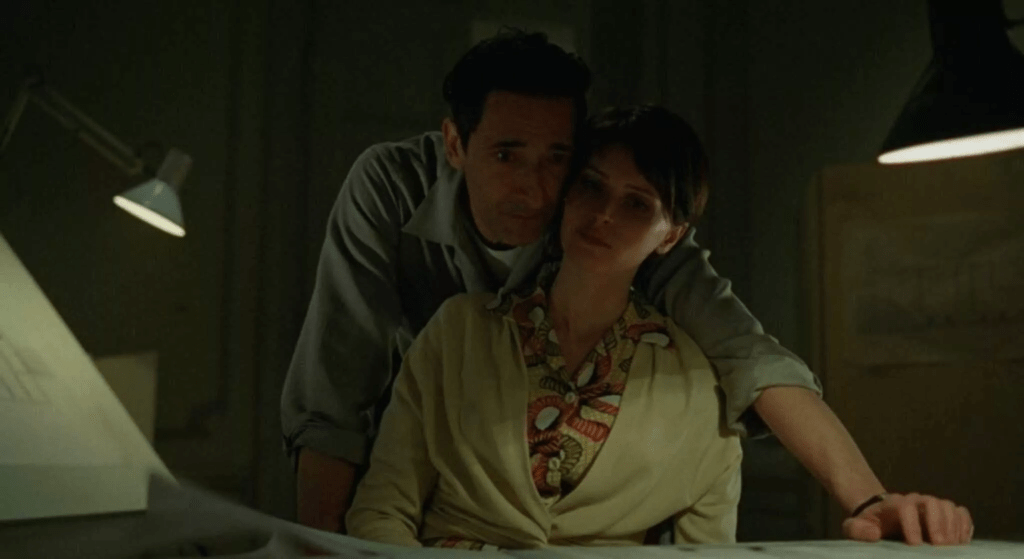

That musical is The End (Grade: A-), starring Tilda Swinton, Michael Shannon, and George McKay as characters known only as The Mother, The Father, and The Son. They live in an giant underground bunker nestled among salt flats with their few staff and friends; it resembles more of an art museum than it does an actual home. From the start it’s clear that in some ways, everyone is telling themselves stories to live, whether they’re aware of it or not. Father worked in the oil industry yet denies that his actions had anything to do with the disaster. The Son – only knowing the bunker – is prepped for the future but how long that future is going to last is never clear. Their routines are jarred with the arrival of Moses Ingram’s Girl, conflicting with their general pronouncements in song that the outside world is full of danger.

What happens is perhaps less important than how everyone feels about it. Oppenheimer’s script with Rasmus Heisterbeg tends towards the anticlimactic but it never feels overly concerned with plot. The Son becomes much more concerned with the “why” of things, why his parents are alone in the bunker, why they decided on their only friends, why they’re writing a history book this particular way. In the grand nature of Hollywood musicals it so often resembles, the characters break into song when their emotions become too complex for any other method. Their movements are less dancing and more the need to express, to shake out the nervous energy. Performance wise, they mostly do good; MacKay and Ingram are the two best singers, while Swinton and Shannon sound unprofessional but not unlistenable. It could’ve used some more musical numbers just to break up the pacing, despite the dialog scenes being arresting. This is the definition of a big swing, admirable in its audacity, made by someone with a deep appreciation for what movie musicals can do and fully embracing all the odd emotional rhythms that come. Of all the films here, you owe it to yourself to at least check this one out; we may never get another one.

In a plesant coincidence (thanks to moving schedules around), Swinton featured prominently in the other big get of the festival, Pedro Almodóvar’s Golden Lion winner The Room Next Door (Grade: B), also starring Julianne Moore. I’ve been trying to catch up on his work, having rewatched and loved All About My Mother and Talk To Her earlier this year; Pain and Glory and Parallel Mothers were two of my favorite films from the past 5 or so years, the latter possibly one of his best works (certainly one of Penelope Cruz’ finest performances).

Unfortunately, as you can tell by the rating, I have to concur with most critics in finding this to be a relative disappointment. All the ingredients for a classic Pedro are here: the enigmatic performances from two fine actresses, the beautifully colored decor, the melodramatic flourishes. But his English language debut is somehow more sedate and subdued than his past work. Swinton and Moore do fine work, as a woman dying of cancer asking her friend to accompany her on a trip so she can end her life, though strangely reserved much of the time. My audience seemed to be laughing at things that didn’t seem like they were supposed to be funny at all, even if some of that excess presents itself (like a scene with a personal trainer). Maybe it’s also that there seems to be little debate over the topic of euthanasia itself, a lack of struggle or buried emotion to burst out. His eye remains as strong as ever, as does Alberto Iglesias’ score. And yes, the rhythms of the dialog do feel slightly awkward and even repetitive at times but honestly I don’t know if it usually sounds this way to a native Spanish speaker. That Golden Lion win was the first time the major festivals have ever given him the big prize; he’s made several much better than this. Still, it’s not without its many pleasures. Maybe he can get Swinton back in Memoria mode and film her in Spanish.

Dialog is not a problem in Flow (Grade: A), because there is none. Latvia’s pick for International Feature is an animated tale of animals traveling on a sailboat in the midst of a massive flood, communicating only via their normal sounds and body language. “Communicating” is putting it a bit strongly, because they all act like normal animals, those innate traits giving them bursts of character in response to each other’s actions, though with some leeway to – say – steer the boat. Our primacy focus is a black cat, acting as cats do as it gets knocked about by all series of torrents and creatures. Joining it are a capybara (very chill), a lemur (obsessed with a basket of shinies), an unidentified bird (injured, acting high and mighty), and a dog (pure of heart, dumb of ass). If this were made by a major animation studio, it’d be a candidate for the most annoying movie alive. Instead, it’s awash in painterly textures, content to sit in silence and calm as it observes the boat move through water. The world feels heavily inspired by games, everything from Ico to Breath of the Wild to Myst and Stray, yet it’s distinctly cinematic, the camera roving through the world and at times adopting a handheld style. What’s more impressive is that a clear narrative emerges, as do conflicts and traits, and by the end you’re rooting for them all to be friends. Can’t say I know for certain what some of the more surreal imagery might be representing, if it does at all. All I know is that I’ll be shocked if I see a better animated feature this year.

I had been planning on seeing Bound In Heaven but due to overrun from both the bumpers and introduction to The End, it started as I was getting out. My backup choice with friends was Hong Sang-Soo’s A Traveller’s Needs (Grade: C), which I probably wouldn’t have seen otherwise. I like Right Now, Wrong Then, so far the only Hong I’ve seen; it’s felt like he’s become a bit of a meme in online circles after that, with his increase in productivity and seeming decrease in actually making a regular movie. If you follow Mike D’Angelo (as I do, check out his website and Patreon), you will be familiar with a lot of his complaints about a lot of Hong’s work lately. Gotta say I agree with him.

Isabelle Huppert’s second team-up has her as a French teacher in Korea with a unique method: having people write down sentences in French that speak to their feelings and practicing those to learn the language. I doubt that’s very effective. The movie itself is mostly in English and it feels like they’re flailing to improvise or the script is so banal it hardly matters otherwise. There doesn’t seem to be much of a plot or really any character build up, just conversations about language and how playing instruments make people feel that go on too long without saying much of anything interesting. Occaisionally he does have some funny moments, like when Huppert leaves one client and they look back to see she’s already gone, commenting on how fast she walks. A later scene involving her boyfriend/roommate and his mom lends itself to some actual conflict and some interest into who she is and why she’s in Korea. It all just comes across as so arbitrary to me, down to the framing and the length of shots. I’ve known that he’s largely doing everything himself now but the image quality itself frequently looks like a home movie. I don’t want to rag on it too much because he has made at least one movie I do like and frankly, he’s made so many others in that time that I’m sure I’ll find another. As it is, it’s just kind of boring, and I’d prefer at least a little more structure and baring that, something interesting or amusing. You can make it look however you want in that case but you can’t have it both ways.

Like most other film festivals, PFF also does retrospective screenings. Usually I don’t go to them, in the past because I could find them elsewhere (and my time was limited), nowadays because chances are they’ve played it before or will play it again. I did, however, decide to go to Streets of Fire (Grade: A-) because I’d already missed it once, and my friend Evan had said I should watch it. I’m so glad I did. Walter Hill’s musical fantasia is pure cinema, exactly as the opening describes: “Another Time, Another Place”. I’ve heard the opening section of first number “Nowhere Fast” a bunch because PFS used it as the bumper for August last year, and I went a ton. The full thing still hits, and kicks off a fantastic sequence in which rock goddess Ellen Aim (Diane Lane) is kidnapped from her band The Attackers by Raven Shaddock (Willem Dafoe, extremely young & incredibly hot), leader of the biker gang The Bombers. It falls to her old flame Tom Cody (Michael Paré), lesbian-coded mechanic and ex-solider McCoy (Amy Madigan), and dweeby manager Billy Fish (Rick Moranis, very surprising) to go and rescue her.

During the beginning and the end, I thought I was watching my new favorite film. Hill fuses the culture and look of the 50s with the hard edge style and talk of the 80s, creating something fully unique in the process. No other film will give you a stripper doing a vigorous Charleston to a bar full of leather-clad bikers giving straightened up Tom Of Finland while a rockabilly saxophonist wails, and frankly the fact that America let it flop is the reason we got Regan a second time. The music – from the operatic pop stylist Jim Steinmann of Bonnie Tyler, Celine Dion, and Meat Loaf – hits hard and hits quick. Once again, I could use so many more numbers. I must admit that my friend was right about the middle. By no means is it bad but it stalls a bit, and Paré isn’t as up to the task of talking, no matter how cool his lines are. But when he’s blowing up bikes with a shotgun… Goddamn is he the coolest motherfucker alive.

Tomorrow: PFF33 comes to an end, with a couple last entries and my favorite 10.